The relationship between animals and their intestinal bacteria is more complex than previously thought. It is known that the host benefits from substances secreted by bacteria. Bacteria live on food in the intestine and on the products of each other's breakdown.

But sometimes there is a third nutritional relationship: there are intestinal bacteria that live only on substances produced by the host itself. Swiss researchers discovered this in an ingenious multidisciplinary study conducted on honey bees. They wrote about it this week in Nature microbiology.

the The intestines of almost all animals Full of bacteria. For example, we humans have Ten times the number of bacteria in our intestines As cells in our body: their total number is about 100 trillion individuals of more than five thousand species, and together they constitute a kilo or two. These bacteria are beneficial: they break down components of our food that we cannot digest ourselves, such as cellulose, produce valuable substances such as vitamin K and keep harmful bacteria under control. In return, the bacteria benefit from a stable, comfortable living environment and all that food in the intestines.

But does the host itself also contribute substances to this metabolic exchange? This is difficult to investigate because of the “overwhelming” amount of material in our intestines, from food to bacterial decomposition products and our own waste products, the Swiss wrote.

Sugar water only

So they looked for a simpler animal model. They found this in the honey of bees.Apis mellifera). It contains only about twenty species of bacteria in its intestines. The bee itself cannot survive on anything but water with sugar added to it. At the same time, it has at least one type of intestinal bacteria that cannot digest sugar. This provides opportunities for interesting experiments, the Swiss believe.

They raised bees without intestinal bacteriaThis is done by allowing it to hatch from the egg in a sterile environment. They fed these bees only sterilized sugar water. They then looked at what happened when different groups of bacteria were allowed to colonize the bees' gut.

They soon discovered that a complex network of relationships was being created in the intestines: different types of bacteria were feeding each other all sorts of substances they had made themselves from sugar. But during one of the experiments, the Swiss came across something strange. In that experiment, only one type of bacteria lived in the bees' gut: Snodgrassella Alfie (Named after the American entomologist Robert Snodgrass, who discovered this species in bees). These bacteria cannot convert sugar. However, this species remained for a long time in the bee intestines.

Chemical analysis of the intestinal juice showed that it contained all sorts of acids, including citric acid and malic acid, which the bees appear to make themselves – after all, they were only fed water, sugar and one type of bacteria. S Alawi They didn't have to expect anything, because they couldn't digest sugar. Can bacteria live on these acids?

To investigate this, the Swiss “sweetened” the glucose molecules in the sweetened water by replacing the relatively light natural carbon atoms with their slightly heavier counterparts. With an advanced measuring tool (Nanoscale secondary ion mass spectrometry(or nano-SIMS) They were then able to demonstrate that these heavier isotopes ended up first in the bee, then in its intestinal juice acids, and then in bacteria that were constantly dividing and growing.

There are likely to be many bacteria that live on substances secreted by their host, the Swiss write – as well as in other animal species. They believe that through these substances, hosts can “steer” the bacterial composition in their gut toward the best possible cooperation. They want to investigate this principle further.

“Coffee buff. Twitter fanatic. Tv practitioner. Social media advocate. Pop culture ninja.”

More Stories

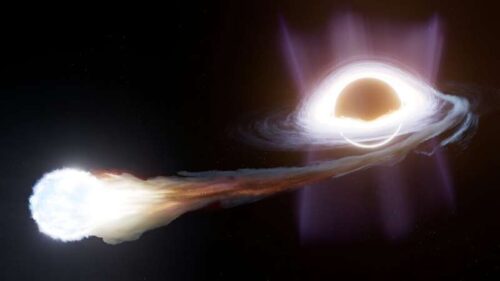

A new way to detect the first stars in the universe

BreinPunt meeting on fall prevention – all the news from Oldebroek

Dark Energy Camera detects a ghostly hand in space